Artificial Intelligence: I Have My Robots Worry for Me (Part 2)

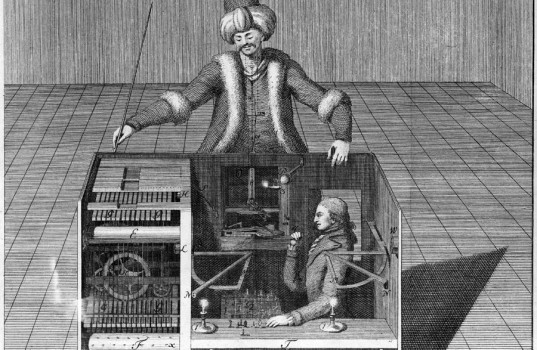

If anyone can be replaced by a computer (as I implied in part 1), shouldn’t I be worried that I could lose my job to one of Asimov’s heirs? After all, project management is just a bunch of data gathering, rules, processes and reporting. I am occasionally accused of being unduly optimistic – and it’s true, optimism in a project manager can be regarded as a character flaw – but in this case I think that optimism is justified by history and logic.

The media has been full of the loss of manufacturing jobs lately. Not all pundits note the facts that the decline started in the 1970s and that automation is the culprit; but leaving that aside, my readers will not need to be told that jobs in professional and services fields have swelled in the same period, more than replacing those lost in manufacturing (if you really need a source, and aren’t prepared to wade into the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ site, The Atlantic has a nice graph). Yes, people will become unemployed, probably some people you know, and that will be painful to the individuals and will have far-reaching social costs that we need to be prepared for. Since the beginning of the industrial revolution people have watched their jobs disappear to automation; but in the long run whenever automation disrupts an industry the economy responds with more (and better) jobs overall.

This is the conclusion recently reached by The Atlantic, The Washington Post and Wired, among many others, and while there are those who argue that it’s different this time – the singularity is nigh – most writers believe that while AI will cause a lot of disruption the overall pattern will hold. The lesson of history is not to fear that jobs might be lost, but that your job might be lost. Most days we need to spend our time and energy working on maintaining the current trajectory so it’s hard to prepare for change. But if you have a plan B, the day you learn you need one is a day you’ll be able to take in stride. In last week’s editorial about lifelong learning, The Economist’s prescription for that day is that “all adults must have access to flexible, affordable training.” The old dog may need to learn some new tricks, but if one is prepared for a little log-rolling, there will be work to do.

Not just work, but more stimulating work. In another article, The Economist argues that automation “…raises the value of the tasks that can be done only by humans”. There are a lot of things I do from day to day that are tedious and repetitive: meeting agendas and notes, status reports, etcetera. While the pain of drudgery is greater at the bottom of any org chart, it exists to some degree from the bottom to the top. Automation changes the way work is done, but it always starts with the donkey work. This leaves the work that only humans can do – and constantly redefines what that means in more complex and sophisticated ways. Data science wasn’t even a field until a few years ago; now it’s possible because data collection evolved from pen and typewriter, through web form, to a bewildering variety of sensors. That doesn’t mean the only jobs left will be for rocket scientists and brain surgeons (although that could be a bad example – medical experts are among those fields being joined by throngs of AIs). The Guardian came back from the Davos conference pleased that under threat is “the boss’s job, not the gardener’s“; I at least agree that it will be a while before we replace hair stylists, waiters, police officers, kindergarten teachers and farmers. In fact, it’s getting difficult to think of any job that will be substantially unaffected by artificial intelligence.

Jobs will change but the tools we have to do them will make them more interesting. Robbie the Robot will get the grunt work; you get to supervise. Others reported from Davos that “About 92 percent of workers expect that the next generation will work very differently because of changes caused by advances in technology. And 87 percent believe these changes will improve their experience of work during the next five years.” Lawyers get their e-discovery done better and in a fraction of the time; doctors can read more scans with fewer errors; editors’ AIs churn out the routine reports, leaving the features to human reporters; and a hundred accounting tasks can be done error-free allowing the accountants to do whatever accountants think is interesting, who really knows.

And getting back to those underwriters, implementing AIs will enable rating to consider more complex inputs with greater accuracy, making finer definitions of the exposures and better assessments of risk. That will leave the pros with more time for the strategic work around development and distribution of insurance products. Will I welcome our new robot overlords? Certainly not, but I will definitely welcome my new Artificially Intelligent underlings.

One Response to Artificial Intelligence: I Have My Robots Worry for Me (Part 2)

Leave a Reply

« Artificial Intelligence: I Have My Robots Worry for Me (Part 1) Better Living Through Artificial Intelligence: Applications That Can’t Come Too Soon »

[…] But just because you could be replaced by a computer, that doesn’t mean you’ll be out of a job. I’ll talk about this in part 2. […]